The State of Music Distribution in China

This article was also published on Hypebot

The Recent Past

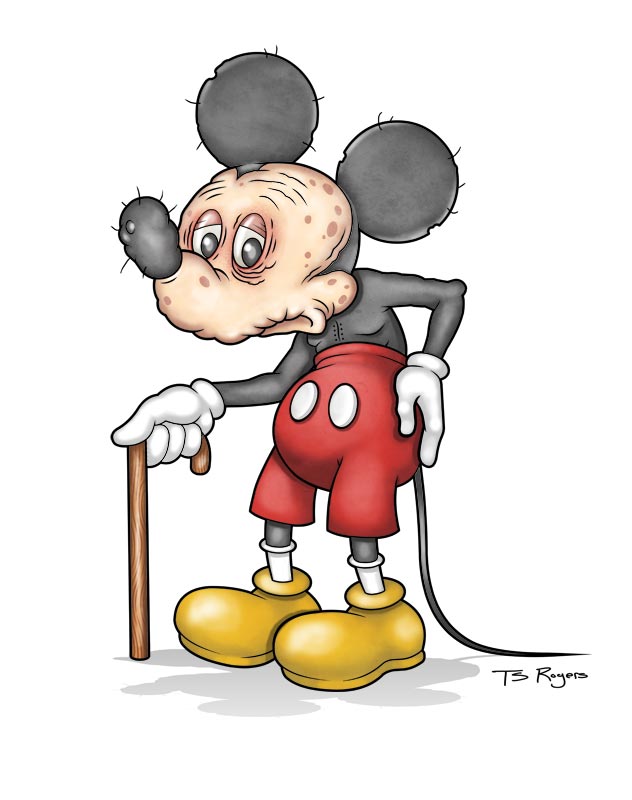

Much of the initial enthusiasm that accompanied the opening up of the Chinese music industry with the advent of the internet, usually supplemented by a hopeful but misguided reference to 1.3 billion people parting with their money, has since whittled down to a more pragmatic approach. Over the past few years, China’s music industry has seemed to vacillate between cautious optimism and a modicum of despair.

The intervening years, during which mega companies like Baidu exploited the works of musicians for their own profit, seem to have left many jaded and a sense of defeatism has numbed many musicians into receiving any sort of remuneration, if at all. Every single music service currently operating in China has its roots in a pirated model.

A few years ago, there was a blaze of publicity perpetuated by Baidu that it had finally turned legit, and endorsed by the major labels, which were no doubt facilitated by sizeable payoffs to turn a blind eye whilst Baidu willfully continued to pirate the music of non-major artists. Since then, Tencent’s QQ Music has been one of the first big music services in China to attempt to become a more large-scale legitimate service, by starting to license the majority of the music it carries. Subsequently, one by one, the other music services started to pay licensing fees for some of the music they carry, often paying high advances to top artists and labels, but low fees to mainstream artists and labels, and pirating the rest.

Now

The main players currently are Tencent’s QQ Music, China Music Corporation’s Kuwo and Kugou, Baidu Music, Alibaba’s Xiami and TTPod (Tian Tian Dong Ting), Duomi, Douban FM, and NetEase (Wangyi) along with mobile telcos China Mobile, China Unicom, and China Telecom. None of the global music services such as iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, Rdio, Deezer, etc. are available in China.

Smaller labels are at a distinct disadvantage, as China’s music services are often reluctant to pay them anything even though some of their music might be blatantly carried by these music services illegally. Foreign labels and distributors are also discriminated against, with music services claiming that few listeners bother about international music so as to avoid paying license fees or at least to keep them at a minimum. This might ring true for music by some artists, but for others like Adele, this is simply a lie told well.

The streaming and download figures displayed on numerous services, which are all unverified, include fake numbers and are influenced by close cooperation with selected labels. In some cases, it’s the music service pushing select artists who they believe could help drive more traffic.

Whilst a lot of the attention outside China has been about the rise of streaming and the accompanying bitching about payouts, China has forged its own path, with many adopting streaming in conjunction with the near-death of physical products accompanied by the winding down of downloads. With the relatively low adoption of mobile 3G in China, for practical purposes many cache 30-50 songs on their mobile phones from streaming services for listening on the go. Once 3G/4G becomes mainstream, mobile streaming will be even more dominant.

Market Size

Physical product has been on a downward spiral and according to the IFPI, CD retail shipments totaled only 2.5m units in 2014, down from 3.6m in 2013 and generated only $13.1m in revenue for the labels.

Based on trade activity, the IFPI reported that digital income rose to $91.4m in 2014, from $82.2m in 2013. Estimates for past annual earnings of the telcos from music put the figure at around US$30m but this has dropped in recent years, and will continue to do so.

Music and Copyright’s recent China Music Industry report had the following caveat on trade and retail differences:

“Assessing China’s recorded music industry by record company earnings tells only half the story, given that there is a big difference between trade earnings and retail sales. When physical soundcarriers were dominant, trade revenue and retail sales differed by around 30% because of the retail markup, but, for some digital formats, the difference between the trade and retail prices can be significantly larger.

Music subscription services in China pay advances to rights holders and offer minimum guarantees that may not be recouped. This means trade revenue figures often inflate the actual value and popularity of the services. In contrast, mobile personalization through ring tones and ring-back tones (RBTs) generate little in trade earnings for rights holders but are a significant, if decreasing, income source for telecoms operators, since rights holders receive only a tiny share of the retail price of the two mobile formats. Measured in terms of actual consumer spend on recorded music, mobile personalization is likely to still account for the biggest share of total recorded music spend. “

The Digital Distribution/ Content Acquisition Model

This article covers only digital distribution, as physical has become very much a niche product in China.

Digital distribution in China by definition is a misnomer in many cases. Global mainstream music services receive their audio files from labels, distributors, and assigned content aggregators after contracts have been signed. But in China, most music services acquire music audio files and metadata – from non-label sources via in-house content farms that till the internet and download the music they require, sometimes via darknets – without any licensing contracts being signed, ie. illegally. Using a combination of crawler software to siphon large quantities of audio files off the internet, and downloading files via sheer manual labor from various sources on the internet, music services then use these to populate their library, which are then brazenly made available to consumers.

The role of distributors, labels, and publishers in China includes pursuing these music services and hashing out a suitable deal. Even after a deal has been struck and with the distributor/ label ready to deliver content directly to these services, many of these services continue to maintain their content farms as their main source of audio files and metadata. Most Chinese music services are unable to process XML or DDEX formats for ingestion, making it harder for international distributors to tap into these music services directly. QQ recently experimented with a self-uploading platform targeted at independent artists, but it is unclear whether there is a revenue-sharing component for artists.

With limited means of monetizing music directly, combined with inefficient content management and bad metadata, this has meant that music services in China are interested in carrying only a finite number of tracks in order to reduce their overheads whilst maximizing the exploitation of user traffic. For example, QQ has an estimated 4m tracks, followed closely by Kuwo at nearly 4m, and then come all the rest, with 1-3m tracks each. This compares unfavorably with the 35m tracks on iTunes and more than 25m on Spotify globally. It is worth noting that there are at a maximum between 250,000 and 300,000 commercially viable Chinese songs, so any expansion in terms of content would have to involve international music.

So the question is, are Chinese users ready for infinitely more content if the necessary infrastructure for metadata, artist information, and promotions that will make all this additional music relevant to users, is not there? Or will this just be an ‘arms race’ for the various music services for marketing purposes or to point missiles at each other in terms of exclusive content? There are only a couple of true music distribution companies in China, yet distribution contracts are being signed and announced by various other music services with no existing distribution teams – a bizarre situation indeed.

This can only mean that content is being signed as bargaining chips between rival music services and as a front for acquiring exclusive content for these services under the guise of ‘distribution’. On the plus side, this might also result in music services and distributors aggressively policing their content against piracy, a situation that few could have imagined a few years ago. But the flip side is that artists whose aim is to make their music accessible to as many Chinese fans as possible are going to be frustrated.

The Business/ Consumer Payment Model

Currently, all music services in China offer music to consumers for free. For some, the music service is merely an appendage by which to draw in user traffic, which they then divert and monetize by other means, especially for the bigger portals like Baidu. It is rarely about the music at all, which is a sad state of affairs for the purist.

So the race is on amongst the various music services to quickly draw in more consumers and with the least amount of resistance, and hence their adoption of the free model for now. For the pure-play music services, advertising is one of their main sources of revenue, but with shrinking CPMs, they are often tempted to find less savory methods to monetize the traffic. There are also partnerships with the mobile telcos, hardware manufacturers, and other companies, but these bring in relatively small revenues.

With free music, there is little incentive for companies to either improve their services or increase their catalogue size, as these would add on to costs but bring in only marginal returns of increased revenue. In the long term, with the current infrastructure model and low CPMs, free music does not appear to be a sustainable model for pure-play music services if there is no clear upgrade path to higher-value paid music, especially once they start paying content owners actual revenue based on the true valuation of content. Music fans will also be left unsatiated, as there is little incentive for the services to improve their service and expand their music offering.

Currently, there is a semblance of premium services labelled as VIP tiers offered by some of the music services, but these are only token offerings with minimal benefits and are not sufficiently differentiated from the free services and hence suffer low take-up rates. Costing RMB 5-10 (US$1-2) monthly, the common thread in their premium offering seems to be high-quality audio at 320kbps with no advertising and the opportunity to buy priority concert tickets. For an audience inured by an onslaught of ads in most of their online activities and not bothering about audio quality via their devices, these benefits are unattractive and have not moved the needle at all.

Mobile

Ringtones and Ringback Tones are not really about music per se, and bring more value to the mobile telcos than to the labels in terms of revenue. It is also said that consumer purchases of Ringback Tones are not a mere organic affair, as the telcos have been known to sometimes force these products onto their customers, especially during festive seasons. For the top artists selected for the exercise, it still delivers good revenue, but on the whole, a downward trend has been noted in the consumption of Ringback Tones.

The telcos have a limited library and will only take in music they deem worthy of their limited virtual shelf space. For each track they ingest, they will also have to prepare it into about 20 different mobile audio formats, leading to physical resource constraints that dictate their reluctance to open their door to content from every other label. In addition, there is a high burden of proof of ownership on labels and publishers with the need to supply supporting authorization letters from all rights holders and companies involved, all the way up to the artist level, and this creates a further barrier.

Publishing Rights

There is a specialized line of distribution for the often ignored but critical area of publishing that has developed in China. There are probably only two distribution companies in China that are capable of understanding and managing this area of distribution of publishing rights. It is also important to note that some of the major publishers and other sizeable independent publishers have not assigned their digital rights to the collection society, Music Copyright Society of China (MCSC) and instead have engaged independent distributors to this task. Whilst the MCSC is already covering a lot of ground, the content of many other publishers needs to be policed, which they assign to individual distributors in China to negotiate and deal directly with the music services to license accordingly. Most of these deals are on a negotiated advance payment basis (see also Royalty Reporting section).

Music Video Services

With a more stabilized digital video landscape having developed over the past couple of years, the main players that carry music videos are Yinyue Tai, Tencent Video, Youku/ Tudou, Baidu’s iQiyi, Sohu Video, Ku6, and LeTV. Even though these services have licensed large numbers of long-form video content like TV series and movies, they are still lagging in terms of licensing music videos and paying fair revenues.

Although most of them — with the exception of Yinyue Tai, Tencent Video, and Youku/ Tudou — carry only a small percentage of music videos relative to their total content, distributors, labels and publishers will still have to negotiate with all of them for due advance payments, as they are usually using these music videos without prior licenses. Youku/ Tudou carry many music videos but is reluctant to pay the labels for them, and will simply take them down when asked to share revenue. Yinyue Tai, one of China’s biggest music video sites, is currently facing problems with paying rights holders their due license fees; this is a situation to be monitored.

Even though internationally YouTube has been accused of paying low rates to rights holders, it has a more robust monetization and content ID copyright monitoring system than these Chinese video services. Until more effort is devoted to developing the monitoring system and installing a proper payment system, distributors and labels will just have to negotiate with each music service individually, though the revenue returns are not likely to be significant for now.

Royalty Reporting

Royalty reporting, or the lack of it, is one of the biggest areas holding back the long-term development of a healthier music industry ecosystem in China. Currently, China’s music services do not provide royalty reports or have systems that properly track music consumption by users. Licensing transactions are based on negotiations, which lead to upfront advances, and in most cases, these are simply buyout payments. Moreover, the music services do not provide any further revenue above and beyond these buyouts, as there is no proper reporting mechanism in place for labels and publishers to review if these amounts have been recouped.

More critically, the lack of royalty reports makes it difficult for labels and publishers to subsequently distribute the advances received and pay their artists and writers. However, for most international artists in the short term, any divvying up of advances as royalties should be welcome for now, as in all likelihood, they might be receiving more than what they were entitled to for their likely minimal number of streams or downloads in China.

On the mobile telco front, China Mobile and China Telecom are more regular with their line-by-line royalty reports, which are usually delivered 3-6 months after the transactions, but China Unicom has been messier, with its reports being as late as a year.

What Next?

The music distribution market is currently in a state of flux but is moving into an exciting phase. Relatively large amounts of money are being paid for some of the more sought-after artists and label repertoire in the short term but the music of other artists is being used without proper licensing or remuneration.

However, without better accounting and royalty reporting by the music services, there are going to be injustices that imply the new model is not much better than the old model in the long term if the infrastructure is not developed to ensure that artists and writers are paid more equitably. An ‘arms race’ to sign up more content either in the guise of ‘distribution’ or as exclusives will only benefit artists in the long term if proper promotions and artist information are developed alongside it.

Mathew D is the President of R2G