[This article was first written for the MidemNet blog to coincide with my panel appearance at Midem 2008 as a means to highlight observations of certain aspects of the market and also to offer words of advice for labels seeking digital licensing opportunities in China and was first published on OUTdustry and it has now been updated for 2009.]

As Olympic hosts and country-of-honor at MIDEM 2008 and Canadian Music Week 2009, China’s music industry is an increasingly common feature on the western agenda. There is, however, almost a whiff of the ‘Wild East’ in the way companies are approaching licensing in the Middle Kingdom.

It has to be realized that the vast majority of Western labels are probably currently unscathed by piracy in China and that’s likely because their music is so obscure in the Chinese consciousness that they have not even had the dubious honor of gracing the servers of China’s notorious MP3 search engine, Baidu.

Piracy in China often gets a lot of attention but many forget the other P’s of marketing and these are the basics that labels intending to come into China should first focus on. For dramatic effect, let me first quote Tim O’Reilly when he said that,

“Obscurity is a far greater threat to authors and creative artists than piracy”.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that one is worse than the other as it is a case of horses for courses. I would also add that in China, in true Darwinian fashion, one man’s piracy is another man’s marketing. But as O’Reilly explained, piracy eventually develops in a manner akin to progressive taxation in exchange for greater exposure and appeal: There is always the regretful possibility that one may eventually despair at the crossroads of Robert Johnson.

Ed Peto’s piece about the Music Business in China also noted the labels’ part in engendering piracy in China,

“The arrival of western product in the early 90s came courtesy of “saw-gashed” CDs: Excess stock and deleted titles from western majors attempting to avoid taxation and disposal costs. These CDs had their cases cut to mark them as defective and were then shipped in to China through free-market economic ports like Guangzhou, only to end up on the black market. An end result that can be seen as a partial shooting-in-the-foot for the western majors who then had to come in and fight against the pirate networks they inadvertently helped set up.”

Kaiser Kuo, one of the pioneers of China’s rock scene added, “During the 1990s they were an important source of foreign music.”

And so, this rejected music from Western shores – a good proportion being hitherto obscure – has bizarrely taken root in China while the majors also propagate low common denominator fare like the Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears, Celine Dion, Sarah Brightman et al in CD stores. A recent alumnus of this group, UK’s X-factor winner Shayne Ward was in Beijing this week and was awarded a Gold Record for sales of 15,000 for his new CD “Breathless”.

The major labels are still counting on physical distribution to help make their numbers in China and International Marketing Director at Universal Music China, Danny Sim has worked tirelessly to develop the market for international artists. In 2007, by his accounts, his efforts resulted in “a significant increase in revenues for CDs and I expect it to be even greater in 2008″, but in general international artists still account for probably less than 10% of the majors’ overall digital revenue in China. As more Chinese are being exposed to Western music via the internet and the media playing more Western music, Danny also hopes that the labels and SPs can work together to cultivate music genres and themes instead of single song hits.

However, this cannot happen in a vacuum and other Western labels who do not have the benefit of an existing network in China will have to do their part to sow the seeds in areas that are often taken for granted like pro-actively providing artist information in Chinese, building artists’ websites in Chinese and in general, stimulating more literature and musical discussions about artists online.

The following is an important checklist for labels intending to come to China and illustrates the prior requirements before their music even tempts the pirates: (Press Play and Flash will play automatically)

In this chart, ‘Music’ refers to whether the song is present or absent on the Chinese networks and highlights the necessity to take control and seed the song in China as the first step. Even if the label has not managed this, third parties might already have done so, which gives rise to the pirated presence. Only when the content has been put in front of the consumer in a meaningful way can they judge whether it appeals to them or not. There are multiple applications and formats in which music manifests itself in China and the challenge in the last mile is to manage the revenue collection or at least ensure that the application mix results in net positive revenue overall.

It is of paramount importance that an infrastructure is developed wherein information about artists is propagated combined with recommendation engines to guide the user along in unfamiliar territory. Ian Rogers recently lamented the death of the album cover, but in China, a more profound barrier exists that stunts the dissemination and understanding of Western music: The lack of basic and standardized metadata including genre classification that allows listeners to recognize song titles and artists.

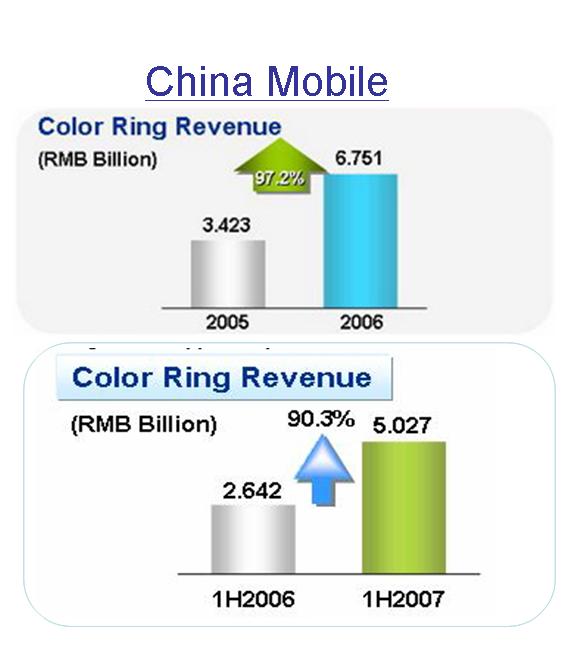

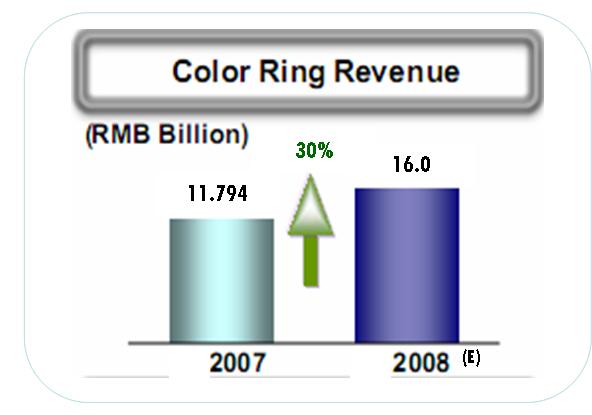

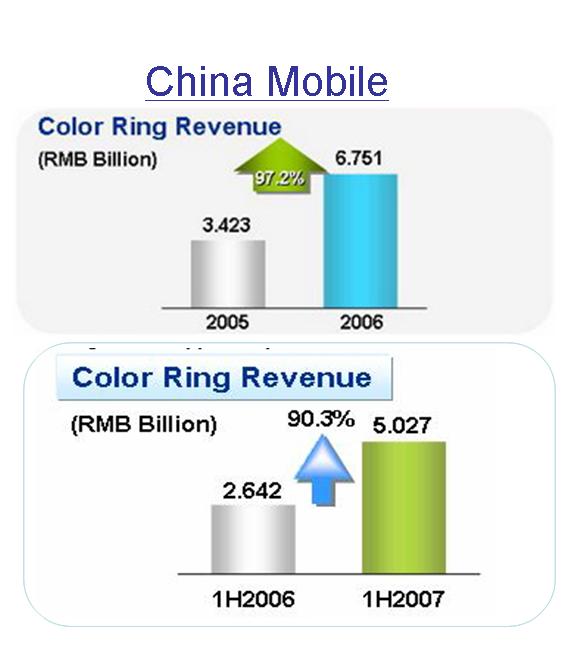

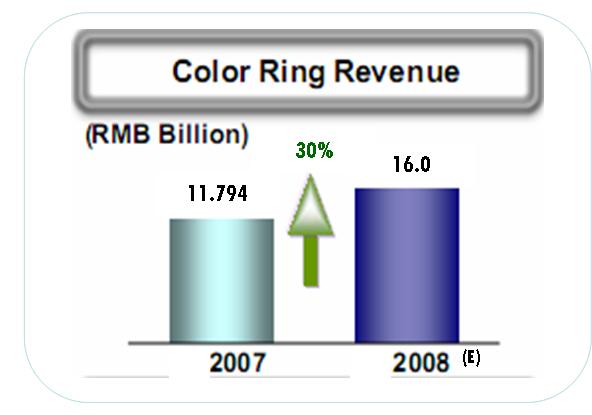

Much fuss has been made about the impressive revenue from mobile music in China – iResearch estimates that Service Providers (SPs) and Content Providers (CPs) earned up to RMB 3 billion (US$400 mil) in 2006 and China Mobile reported revenues of RMB 11.8 billion in 2007 for Caller Ring Back Tones (CRBT) alone and probably an estimated RMB 16-18 billion (more than US$2 bil) for 2008, but before prospectors start packing their digging tools, it is important to note three facts:

1) Of all the mobile applications, Caller Ringback Tones (CRBT) generate the largest revenues but it has to be noted that the bulk of it goes to China Mobile. When a user first subscribes to their CRBT package of choice (from one song to ten), only the first sign-up fee is shared amongst China Mobile, the SP, the distribution, the label and the music publisher after which the full monthly subscriptions of RMB 5 goes solely to China Mobile. However, substantial amounts can be made by top Chinese singers who can sometimes sell between 10 to 20 million CRBT subscriptions, but this is a rarefied space that is not breached by Western artists.

(Graphics by China Mobile. Note: In Chinese lingo Color Ring = Caller Ringback Tones)

2)The bulk of the revenue in mobile music is being garnered by Chinese music albeit dominated again by low common denominator fare – and I do suspect that the rural population does sway the popular vote. An examination of the CRBT sales charts for 2007 reveals a dearth of non-Chinese tunes with notable exceptions being Groove Coverage’s ‘God Is a Girl’, with 2004/05 hits Michael Learns To Rock’s ‘Take Me To Your Heart’, Emilia’s ‘Big Big World’ and Backstreet Boys’ ‘As Long As You Love Me’ still earning residual revenues in 2007.

3) Small CPs and especially Western CPs are at a natural disadvantage in negotiating deals with SPs and regardless of whether a deal is struck, there is every possibility that the CPs’ songs (assuming that they have sufficient appeal) will appear on SPs properties for distribution/sale. And it being an extremely time consuming and technology intensive effort to find out who is pirating the songs, and also to verify how much is being actually made by existing SP partners, CPs are likely to realize much lower revenues than those actually being earned.

William Bao Bean, analyst at Softbank China has calculated that such slippages or under-reporting of revenues to CPs averaged at between 20%-35% while R2G’s close monitoring via its proprietary system has caught a number of SPs under-reporting CRBT revenues by as much as 50%. It is thus critical that a trusted music partner is sought in China in order to maximize one’s revenues whilst monitoring accounting piracy levels.

Mobile for now seems to be the domain of Chinese music so Western labels coming to China would do well to invest and focus on developing their training wheels in other areas so that they too can make the leap into this relatively more lucrative arena.

The Chinese song universe is estimated to be not more than 300,000 and with a smaller commercial subset with the potential to provide meaningful revenue – and in discussions that some of us had with Chris Anderson during his trip to Beijing in Dec 07, he also concluded that there is currently no Long Tail of Music in China. This Long Tail WILL evolve in China and will be populated by international music and this is where the opportunity lies. Evolving tastes and growing individualism are already seeing Chinese listeners trying seek out non-mainstream music, but this music is poorly represented on the free networks and that is an opportunity to be tapped by Western labels.

It has to be realized that almost all full-length mainstream music in China is currently being downloaded for free, facilitated by P2P networks and search engines like Baidu and Yahoo (who have both already been found guilty of infringements by the courts). And until music labels pro-actively put in more effort to inhibit Baidu’s ability to illegally deliver music, the few existing paid full-length music retail download stores will have a hard time. However, I do believe that with better metadata and genre classification, music education and accessible representation of some of this niche music eg. classical, jazz, heavy metal, punk etc, a paid model at fair prices can exist.

Tim O’Reilly encapsulated it best in 2002,

“Services like Kazaa flourish in the absence of competitive alternatives. I confidently predict that once the music industry provides a service that provides access to all the same songs, freedom from onerous copy-restriction, more accurate metadata and other added value, there will be hundreds of millions of paying subscribers. That is, unless they wait too long, in which case, Kazaa itself will start to offer (and charge for) these advantages. (Or would, in the absence of legal challenges.)”

For ‘Kazaa’ read ‘Baidu’ and certainly, China is currently in such a situation where if a viable alternative is not delivered soon, the opportunity will be hijacked by less well-meaning entities. Labels who are seeking to move into China should first seek trusted partners and forget about seeking a quick buck via minimum guarantees or advances and instead should help to build up the infrastructure accordingly. Labels that do not do their homework will inevitably get burned by unscrupulous partners.

Likewise, licensing music for streaming to SPs will only provide returns if there is sufficient marketing support for the artists and also supporting literature and metadata. For example, one of the top music streaming sites 1ting.com records Avril Lavigne’s Girlfriend as the top ranked English song for 2007 at a lowly position of only 132 with 25,000 streams. The top song for 2007 registered 3 million streams in comparison.

In conclusion, it is important to note the following:

1. China offers its opportunities but when a new Western label comes into town, it naturally falls into the Long Tail.

2. The Long Tail will be a black hole unless the supporting information and tools are provided to help the labels’ acts stand out.

3. This will involve working with a trusted partner who not only knows the China market but also understands the label’s culture and potential of its acts. It might possibly also involve sharing of investment and development costs.

4. Giving away music is not the solution – there is potential to develop a paid model with a valued service. The search engines would have us believe otherwise as befits their objectives.

There is no silver bullet in music for China and the gold at the end of the rainbow can only be mined with a proper infrastructure supported by the labels and retail partners.